by Emma Gilmartin

During my time as a PhD student, starting in 2015, Fund4Trees awarded grant funding to support our research on fungi in beech trees. I am pleased to provide an update on the completed project.

Previous research, including lab-based growing fungal cultures from wood, and early-stage DNA technology of the early 2000s, all showed that some wood decaying fungi were latently present in living wood some time before decay development. But, as new DNA sequencing methods became available, we hoped to explore this in more detail. So, as part of a bigger project on beech heart rot and the hollowing process, we set out to learn more about the fungi present in the sapwood of living beech trees. However, the research was not without its challenges, as reflected on in an earlier blog post.

In the summer of 2017, we sampled 66 living beech trees at ten sites across England and Wales. Most of those trees were sampled just once, at a single point on the southern aspect of the trunk at 1.3 metres above the ground. Five trees were sampled more than this — thirteen times each — around the sides of the trunk and up into the branches of the crown to about 20 metres above the ground. The sampling involved the scrupulous (an understatement) method of sterile extraction of living sapwood by running a drill through a collecting tube placed against the wood after we had removed the bark. We sterilised every piece of our kit before collecting each sample to avoid contamination from the surroundings, usually woodland. We needed to ensure that the results were real and did not include fungi that had ‘crept in’ from the air, our clothes, the lab, and so on.

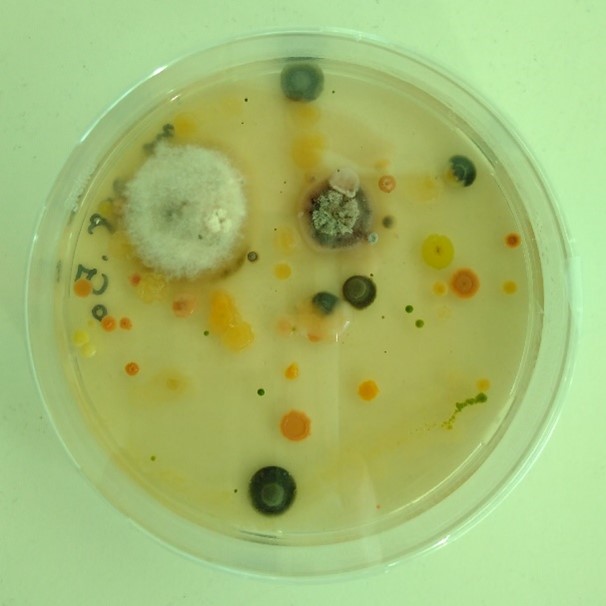

After collecting the samples, they were frozen and sent to Madison, Wisconsin. But only after I had taken a proportion of each sample for culturing in the lab at Cardiff University. Laboratory culturing involved adding a very small sample of the drilled wood dust to Petri dishes and then watching to identify what grew from those tiny pieces. Culturing is laborious work; each outgrowth on every petri dish had to be separated to be grown on and individually identified through DNA barcoding.

I was later reunited with the frozen samples when I spent time with researchers Michelle Jusino, Mark Banik and Dan Lindner, based at the national research laboratory of the US Forest Service. I was there to learn from their significant expertise in fungal community sequencing. It took us a month, spent in the basement of the Forest Products Laboratory, to extract the DNA from these samples and prepare them for a DNA sequencing technique called metabarcoding.

Laboratory work. Example of Petri dish showing growth of a range of fungi and bacteria from one tiny sample of drilled wood dust (top). The imposing Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin (bottom).

Our paper gives the results of our exploration into the sapwood of beech trees. It describes how the fungal communities we found differed according to the research method (e.g. DNA metabarcoding vs. isolation of fungi into culture), between sites and between individual trees. It surprised us to find that wood decaying fungi were detectable in 80% of our samples. The species detected included some well-known decayers of beech wood, including Ganoderma, Meripilus and more. The long list of endophytes that could go on to decay beech wood demonstrated that fungal spores or mycelia are present throughout these trees in their sapwood before any dysfunction or decay has occurred.

I hope you’ll enjoy reading the results in more detail! These are published in a paper in the journal Fungal Ecology, thanks to support from Fund4Trees.The paper is freely available to download here, and my final PhD thesis is also accessible here.